Embedded systems are everywhere. A digital watch, microwave oven, electronic toy, and your car dashboard are a few disparate examples. The characteristics of an embedded system are:

- Made from a combination of hardware and software

- Task specific. They’re designed to perform one specialized task as opposed to general purpose computers

- Usually reactive or feedback-oriented. E.g. most home or kitchen appliances only function when you interact with them.

- Built with efficiency and frugality. Your toaster needs a timer and heat control, but it really doesn’t need a full-fledged CPU

- Should be reliable and stable. Because they are simple, we expect these machines to work. They shouldn’t require maintenance because it’s often easier and cheaper to buy a new one.

For my required EE Hardware design project, my team developed an embedded system on an Atlys Spartan-6 Development Board. This board constructs your hardware specification, like an FPGA, but then it can also run C software that you place on top of the hardware.

My brother’s Flat Stanley visited me while I was working in the EE lab. Sadly, I couldn’t find a photo of our finished project, but this is our Spartan-6 Development Board

We hooked up a webcam, a screen, and speakers to our Board. We had the screen display the camera’s output. Our game consisted of these playable modes:

- Changes the chord’s duration based on the red/blue/green content of the overall pixel count.

- Changes the chord based the amount of movement detected by the camera.

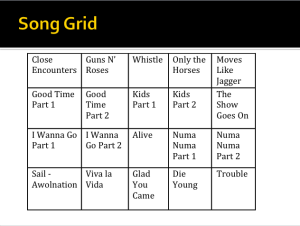

- A grid is overlaid on the screen. When a user in front of the camera covers a square of the grid with their hand, the board plays a song.

Skills:

- Verilog code in Xilinx Platform Studio configures the processor-based system. [The hardware platform managed the transfer of data from the camera to the screen. All the song data was also implemented in hardware.]

- C programming in Xilinx Software Development Kit. [Everything else: the music player, game controls, game logic, pixel computations were done in software.]

Key Takeaway: This project was a turning point: creating the hardware infrastructure was important, but the software was the crux of the game! My specialty was more on the hardware side and I realized that I shouldn’t leave college without delving into the software domain.

DJ mode allows user to mash these pop songs together based on where one’s hand is positioned in the screen’s grid.